Download it Now

Below you can access the Forbidden City audio tours. Or you can download the app directly to your Apple iPhone or Android Smartphone here!

Tour Stop: 1

Forbidden City 3D Printed Model

The Forbidden City is divided into an outer and inner court. The outer court was the setting for the most important state events including emperors’ inaugurations and birthdays, New Year’s celebrations, and receptions for foreign ambassadors and honorary guests.

In this exhibition, the function of the outer court and the important roles of various state rituals are explored through painting, ceremonial costumes, a display of throne-room furniture, arms and armor, and musical instruments.

The inner court was reserved for private activities and also served as the living quarters for the emperor and his family. Informal portraits of the emperor and his family, decorative objects and furnishings and Buddhist and Daoist works of art offer a glimpse into the private and spiritual life of the imperial family. Close

Tour Stop: 2

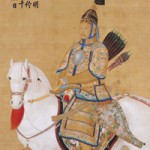

Emperor Qianlong on Horseback, 1758

Qing dynasty, Qianlong period (1736–95)

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

©The Palace Museum

This historical portrait depicts Emperor Qianlong at his first review of the grand parade of the Eight-Banner Army near Beijing in November 1739. The Eight-Banner review was one of the many martial rites, or junli, for strengthening skills and forces. As part of the review, the emperor, military officials and imperial troops would demonstrate their archery prowess–ten thousand soldiers participated in this rite.

Here, the young, ambitious emperor wears his ceremonial armor and helmet. Carrying a sword, bow, and arrows, he sits atop his favorite white horse, Wanjishuang (Thousands of Auspiciousness), a gift from Khalkha Mongolian nobles.

In the first gallery, you can see similar items depicted in this portrait, including weapons, a suit of ceremonial armor, and Emperor Qianlong’s helmet.

This work was painted nearly twenty years after the first Eight-Banner review. In 1758, Emperor Qianlong summoned Lang Shining, the Italian Jesuit court painter, to create this painting. Contrast of light and dark, three-dimensional perspective, and intricate brushwork for the armor and the horse reveal Lang’s distinctive style. This work blends Western technique and Chinese traditional mediums, a characteristic of mid-Qing dynasty court paintings. Close

Tour Stop: 3

Ceremonial Armor with Dragon Design

Satin with embroidery, gold thread, pearls, gilt copper studs, steel, copper buttons

©The Palace Museum

This gallery showcases ceremonial implements associated with martial rites of the Qing court.

The swords, daggers and bows and arrows featured here were made by the imperial court workshops and used by the emperor during imperial reviews of the army, autumn hunts, or inspection tours.

Ceremonial suits of armor worn by the Qing emperors were very elaborate. This suit is made from imperial yellow satin, a color reserved for the emperor. The outstanding embroidery on the armor includes five-clawed dragons in gold thread, multicolor flaming pearls, and other auspicious motifs, such as clouds, ocean waves, and mountains. Golden horizontal plates are woven in gilded strips to imitate overlapping metal scales

Emperor Qianlong rides on horseback wearing an almost identical suit of armor in his portrait at the entrance to the exhibition.Close

Tour Stop: 4

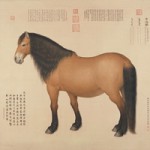

Horse Zizaiju, 1743

Qing dynasty, Qianlong period (1736–95)

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

©The Palace Museum

This is one of two life-size portraits of imperial horses on display in this gallery. Zizaiju (which translates to “at ease with oneself”) was made in 1743 for the Qianlong emperor by Giuseppe Castiglione who took the Chinese name, Lang Shining. A trained portrait painter from Italy, Lang arrived in Beijing in 1715 as a young Jesuit missionary, and his artistic talent led him to a successful career as a court painter for more than fifty years under three Qing emperors.

Although Lang painted many different subjects in court, his horse paintings won him the greatest recognition in Chinese art history. Here, Lang successfully combined his Western training with conventional Chinese methods and values to give his subject both substance and character. Lang’s unique blend of styles was particularly suited for the imperial need of providing visual records of official events, including inaugurations, tours of the South, rituals, hunting trips, and imperial horses or other animals. Lang often collaborated with or taught other Chinese and European painters in the Qing court.

This work, painted when Lang was fifty-six years of age, is based on a realistic sketch and apparently met the approval of the Qianlong emperor. Close

Tour Stop: 5

Returning to the Capital from the series Emperor Kangxi’s Tour of the South, approx. 1695–98

Qing dynasty, Kangxi period (1662–1722)

Handscroll; ink and color on silk

©The Palace Museum

One form of Chinese painting is the handscroll, a continuous roll of paper onto which an artist paints an image in a horizontal format. This monumental scroll belongs to a twelve-scroll series that documents Emperor Kangxi’s second journey to southern China in 1689. The work realistically depicts the historic event and architectural landmarks and also shows seventeenth-century imperial ritual services in and around the Forbidden City.

The scroll unrolls, from right to left, showing the five-mile route from the imperial palace to Yongdingmen, Beijing’s southern gate.

The procession begins with imperial guards and mounted horsemen passing through the gates of the inner city. Outside the Zhengyangmen gate, which once guarded the southern entrance to the inner city, Emperor Kangxi sits in a sedan chair carried by eight bearers, preceded by the marching band and followed by imperial horsemen.

Close

Tour Stop: 6

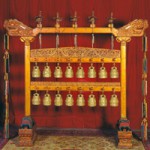

Set of Ritual Bells, dated 1713

Gilt bronze, gold lacquer on wood, painted design, silk

©The Palace Museum

In the early eighteenth century, the Kangxi court conducted an extensive survey of musical instruments and ancient ritual music and then ordered the production of musical instruments for state rituals. This set of bells, used for formal state events, was produced during this period. The bodies of the sixteen gilt-bronze bells in this imperial set were cast with dragons amid clouds and each knob shaped into a pair of dragons.

Though the bells are similar in size, each bell has varying inner diameters and wall thickness and produce distinct musical notes when struck with a mallet along the rim.

Suspended from a golden-lacquered wooden stand supported by a pair of crouching lions, this set of bells was played outside a palace hall during events such as the emperor’s enthronement, sacrifices, and state banquets. With silk tassels hanging from their beaks, five phoenixes stand across the lintel, flanked by sculpted dragonheads. Carved into the lower crossbars are mountains, waves, and a pair of dragons.

Among the most celebrated percussion instruments, stone chimes were played alongside bronze bells during state events as early as the Western Zhou dynasty (1050-771 BC).

The sixteen jade chimes in the set across from these bells are painted in gold with dragons and clouds on both sides.

Close

Tour Stop: 7

Throne and Screen with Dragons amid Clouds

Carved red lacquer on nanmu wood, zitan frame

©The Palace Museum

This red lacquered throne and its matching screen once furnished Yongshougong, which translates to the Palace of Eternal Longevity, one of the twelve residential chambers in the inner court.

The screen was constructed with three nanmu panels and frames of zitan wood, a rare tropical hardwood from the rosewood family. In a scene carved on the center panel, a large dragon leads two smaller dragons amid clouds, symbolizing an emperor leading young princes. Similar carvings decorate the back and side panels of the throne.

The throne and screen symbolized the emperor and served as focal point of imperial power in the Palace of Eternal Longevity. Close

Tour Stop: 8

Portrait of Empress Xiaoxianchun, 1736-38

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

©The Palace Museum

Lady Fucha, born in 1712 to a prominent Manchu family, was married to Prince Hongli in 1727. Her husband ascended the throne as Emperor Qianlong in 1736, and she became empress two years later at her coronation, in 1738. She was renowned for her frugal lifestyle and was regarded as a model empress in the court. In 1748, at the age of thirty-seven, she died onboard the boat carrying her back from ritual services in Shandong Province.

In this large full-length portrait, the empress sits on a dragon throne in an elaborate ceremonial robe. Gazing directly at the viewer, the Empress’s fine facial features allude to her beauty, talent, and grace, and an elevated crown decorated with gold and pearls conceals her hair. She wears three strands of pearls and corals, a headband, a collar band, and a red silk ribbon. The rich jewelry, intricate embroidery, and splendid color reveal the noble status of the empress. Many of the formal accessories depicted in this imperial portrait are on display in this gallery. Close

Tour Stop: 9

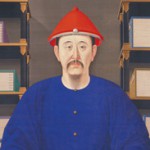

Emperor Kangxi Reading

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

©The Palace Museum

A major figure in the development of modern China, Kangxi learned the rudiments of Western technology from European Jesuit missionaries, some of whom were sent by King Louis XIV of France and served as court artists. This work, probably by a European Jesuit painter, is an eminent example of court portraits incorporating European aesthetics.

While Qing court painters had to abide by strict guidelines for portraying royal subjects with adequate dignity, Emperor Kangxi welcomed diverse artistic creations and European influences in Chinese court art. Together, European and Chinese artists experimented with combining techniques to portray animals, still life, and people.

The scene shows Emperor Kangxi in a symmetrical setting that conveys a sense of solemnity. Soft light emanates from the left, casting gray shadows on the wall, the book, and the emperor’s face. The intense colors of the blue robe, red hat, and white pearl were all calculated to appeal to the emperor.

Close

Tour Stop: 10

Wine Cup and Saucer

Gold with polychrome enamels, two pearls on handles

©The Palace MuseumThe extraordinary painting on this cup and saucer marks it as one of the most exceptional wine sets produced by the imperial workshop. The exterior of the cup and saucer are encrusted with floral motifs in lavish gold, turquoise, cobalt blue, cerulean, green, white, pink, and purple on a lemon-yellow background. With its brilliant color scheme, asymmetrical cascading, and classic designs on the handles and saucer, this set typifies the Qing court’s enamel style, influenced by Louis XVI designs. Many similar elaborate works were created for decoration only, and not for practical use.

Until the late 1600s, the materials used in the imperial workshop to produce luxury items with European enamel were mostly imported. By 1728, the Guangzhou imperial workshop in the south succeeded in producing nine new colors modeled after those from Europe which are exemplified in this extraordinary set.

Close

Tour Stop: 11

Empress Dowager Cixi Taking Snuff, approx. 1860s–70s

or Guangxu period (1875–1908)

Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper

©The Palace Museum

Empress Xiaoqinxian, best known as Empress Dowager Cixi rose from low-ranking concubine to honored imperial consort when she gave birth to a son, the future Emperor Tongzhi. With the support of the court’s conservative factions, Cixi managed to take full control of the government and ruled during the reigns of Emperor Tongzhi and Emperor Guangxu.

Here, Cixi sits under a pine tree in a courtyard and partakes of snuff, a popular activity among nobility in the 19th century. Her robe’s design of a dragon over the Eastern Ocean in the Daoist paradise identifies it as ceremonial attire for an empress or honored consort. Over her left shoulder, a striking ensemble of peonies and nine peaches symbolize good fortune and longevity, suggesting Cixi’s upcoming birthday celebration.

Close

Tour Stop: 12

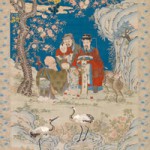

In Praise of the Three Stars, 1782–92

Hanging scroll; cut-silk (kesi) tapestry with silk and metallic threads, painted design

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Mr. Christopher T. Chenery, 64.41

This remarkable silk tapestry from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts collection includes Emperor Qianlong’s prose woven directly into the tapestry and depicts legendary Chinese deities, known as the Three Stars, or the three immortals of happiness, prosperity, and longevity. The man holding a child is the God of Happiness, or Jupiter. To his left and wearing a crown is the God of Prosperity , who is the sixth star in the Ursa Major constellation. He is wearing an official’s robe and crown, and the deer by his side refers to his high rank and promotion. The God of Longevity, a symbol of the South Star, holds a staff and offers the peach of immortality. The children in the scene represent immortal boys. One of them holds a peony branch, a traditional symbol of longevity.

The picturesque scene includes floating clouds, mountains, peach-filled trees, and peonies and chrysanthemum in full bloom. The entire tapestry is woven in kesi, or cut-silk technique. Gold and silver embroidery form the figures’ costumes, and their facial features are painted in fine lines. The integration of cut-silk weaving, embroidery, and painting make this scroll one of the most spectacular tapestries produced in the Suzhou imperial workshops during the eighteenth century.

Close

Tour Stop: 13

Looking into a Mirror from the series Yinzhen’s Consorts Partaking in Pleasurable Activities, approx. 1709–23

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

©The Palace Museum

This painting, along with another on display in this gallery, belongs to a series showing the daily activities of women in the imperial residence.

Here, a female in a Han-style robe sits on a tree-root couch and looks into a bronze mirror. Her right hand rests on a Ming-style warmer. The calligraphy on the screen behind her left shoulder is a handwritten poem by Prince Yong, nicknamed Yinzhen, who would become emperor Yongzheng.

The room is characteristic of a Chinese scholar’s studio, traditionally associated with educated men and the court elite. A place of contemplation, a scholar’s studio typically included a collection of art objects and books and an area for enjoying tea. In this painting, antiques and contemporary works are displayed, such as a 12th-century purple narcissus planter by the window, a 15th-century red-glazed plate containing the fruit known as Buddha’s hand citron, a 17th-century bamboo stool that holds a teacup, and a contemporary water boiler.

Close

Tour Stop: 14

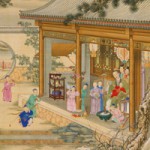

Emperor Qianlong Celebrating the New Year, 1736–38

Qing dynasty, Qianlong period (1736–95)

Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

©The Palace Museum

Qing court painting represents the last great chapter in China’s dynastic painting history. The Qing rulers, being true heirs to the Ming legacy, reinstituted court painters, tailoring the tradition to meet the demands and tastes of their time.

This painting portrays Emperor Qianlong as a young father enjoying the New Year’s celebration with his children in the inner court of the imperial palace. Intimate portraits such as this were regularly produced by court painters in to record events and activities of imperial life, both official and domestic.

Sitting inside a garden pavilion, the emperor holds a baby in his arms and watches his older children play with firecrackers. The baby and the two young boys standing next to the emperor wear small gold crowns that are styled after their father’s, identifying them as imperial sons. The celebration is further enhanced by the emperor hitting a stone musical instrument or jiqing, a term that also means auspicious festivity.

Close

Tour Stop: 15

Music Clock on a Planter with Lotus Pond and Daoist Immortals

Gilt copper alloy with enamel inlay (cloisonné), gemstone, glass, enamel

©The Palace Museum

This clock is one of few works that survived produced by Chinese artisans in the imperial workshop under court-appointed European engineers. Blending European enamel techniques and traditional Chinese motifs, the quality and engineering of this timepiece raised the status of clocks from functional to creative, decorative works of art.

When the clock is wound, the lotus petals open revealing human and animal figures. Referring to the Daoist concept of immortality, a kneeling boy and monkey offer peaches to the goddess, Queen Mother of the West, who sits and enjoys the entertainment.

In 1584, the first Chinese-made clock modeled after the European version was produced in Guangdong Province. When the French ship L’Amphitrite brought more European clocks to China in 1699, the Qing court established its own workshop to make these distinctive timepieces.

Close

Tour Stop: 16

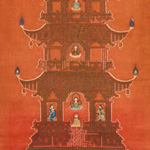

Pagoda with the Diamond Sutra

Hanging scroll; embroidery on satin, gold and silver threads

©The Palace Museum

Ming and Qing emperors and their extended families were pious practitioners of Buddhism and Daoism. The objects in the last two galleries feature thirty works of Buddhist and Daoist statues, thangkas, sutras, models of pagodas, and altar offerings.

Assembled on satin in eight sections, this embroidered scroll depicts architectural details of a seven-story pagoda with multiple eaves. The first level includes a depiction of Shakyamuni Buddha preaching to his disciple Subhuti, who is flanked by two heavenly guardians.

Chinese characters in the standard script are embroidered in dark blue silk. In five thousand words, the Diamond Sutra recounts the dialogue between Shakyamuni and Subhuti and remains one of the most important Mahayana scriptures, favored especially by Chan Buddhist devotees.

Noted for their skills and craftsmanship, the Gu family in Shanghai created this work that exemplifies not only their distinctive needlework techniques but also their devotion to Buddhist subjects.

Close

Tour Stop: 17

Sixteen Luohans, approx. 1777

Sixteen-panel folding screen; zitan framed wood panels, jade inlay

©The Palace Museum

These jade inlay panels depict the sixteen luohans, or Buddhist deities, either seated on a rock or leaning against a tree, reading or meditating. Their bulging eyes, long eyebrows, and prominent noses reveal their divine and earthly natures. The figures carry attributes, such as sutras, rosaries, and shafts, that illustrate their dedication to their faith. Each panel bears the name of a deity, along with a poem by Emperor Qianlong, his signature, and two seals.

In Mahayana Buddhism, an important role for the luohan is to remain in this world to assist others to salvation. Thus, the luohan became a symbol of longevity and dedication. Emperor Qianlong installed this screen in his private chapel in the Qianlong Garden, built for his retirement.

Close

Tour Stop: 18

Vairochana Buddha in Ritual Costume,17th century

Copper alloy, gold dust, embroidered satin, cotton, coral knot

©The Palace Museum

Emperor Qianlong was a follower of Tibetan Buddhism. His personal beliefs greatly influenced his decisions on every aspect of court life. Thirty Tibetan temples were constructed within the residential complexes and gardens of the inner court.

This Vairochana Buddha, the supreme deity in Tantric Buddhism, sits on a double-lotus platform in deep meditation. He wears a three-leaf crown and an elaborate silk robe that conceals his body. He makes his characteristic hand gesture for wisdom, while his facial expression conveys a sense of tranquility and grace. The crown, the broad face, and the wide lotus petals on the base reveal a distinctive style of classical Tibetan imagery that integrated Indian, Nepalese, and Chinese artistic elements.

Textiles were tailored to fit over a statue for worship and protection. The yellow satin robe worn by this Buddha features lotus blossoms embroidered with silk and golden thread, cotton padding, and a red silk lining. His fashion mirrors that of the Qianlong period and represents Emperor Qianlong’s devotion to Buddhist iconography.

Close

Tour Stop: 19

Supreme Heavenly Lord, Thunder Deity

Gilt bronze, pigment

©The Palace Museum

In Daoist legend, the gods of thunder could strike in the darkness, bring forth rain, and convert chaos into order. Dressed in elaborate golden armor with a monster-mask buckle, the Supreme Heavenly Lord is flanked by two deities under his command. These three thunder deities were displayed with five others in a Daoist temple in the palace known as Hall of Heavenly Sky.

The Supreme Heavenly Lord is identified by his white face, third eye, and bare feet. He holds a sword in his right hand and gestures with the other. Standing to his right is Heavenly Lord Zhang, who resembles a birdlike creature. He holds a tablet in his left hand and an ax, now lost, in his right. Marshal Gou is dressed in armor and holds a chisel. Each deity rests on a wooden base with his name and title carved in the front.

Close