Bibliography

“Civil Rights Act of 1957.” Civil Digital Rights Library.

crdl.usg.edu/events/civil_rights_act_1957/?Welcome

“Civil Rights Act (1964)” Our Documents.

www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=97

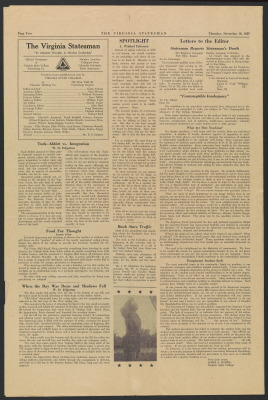

“Commencement.” Virginia Museum of History & Culture.

www.virginiahistory.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/commencement.

Hershman, James H., Jr. “Massive Resistance.” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, 29

Jun. 2011. www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Massive_Resistance. Accessed 12 Dec. 2019.

“I Have a Dream.” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Stanford

University. kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/i-have-dream

“Letter from a Birmingham Jail [King, Jr.]” African Studies Center – University of Pennsylvania,

www.africa.upenn.edu/Articles_Gen/Letter_Birmingham.html.

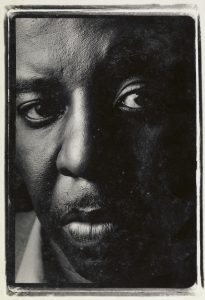

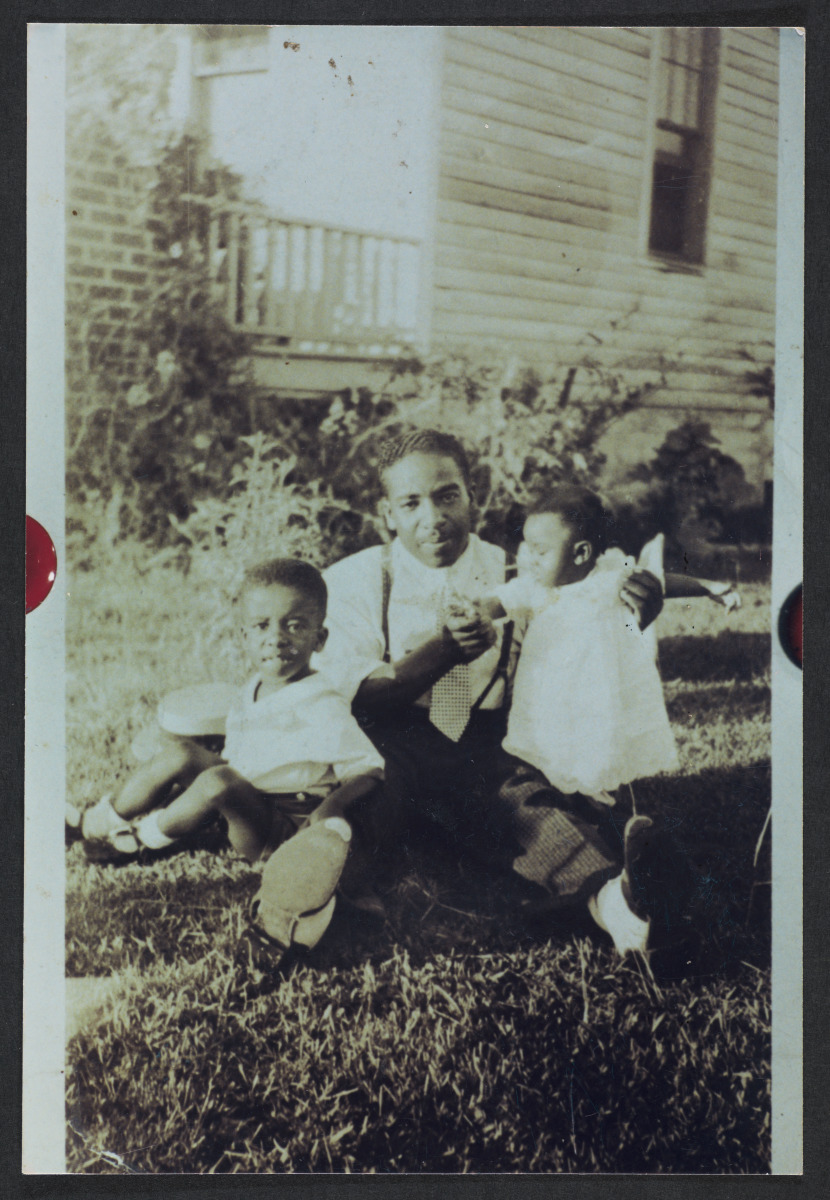

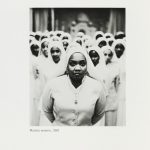

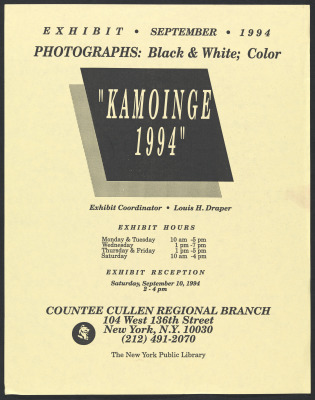

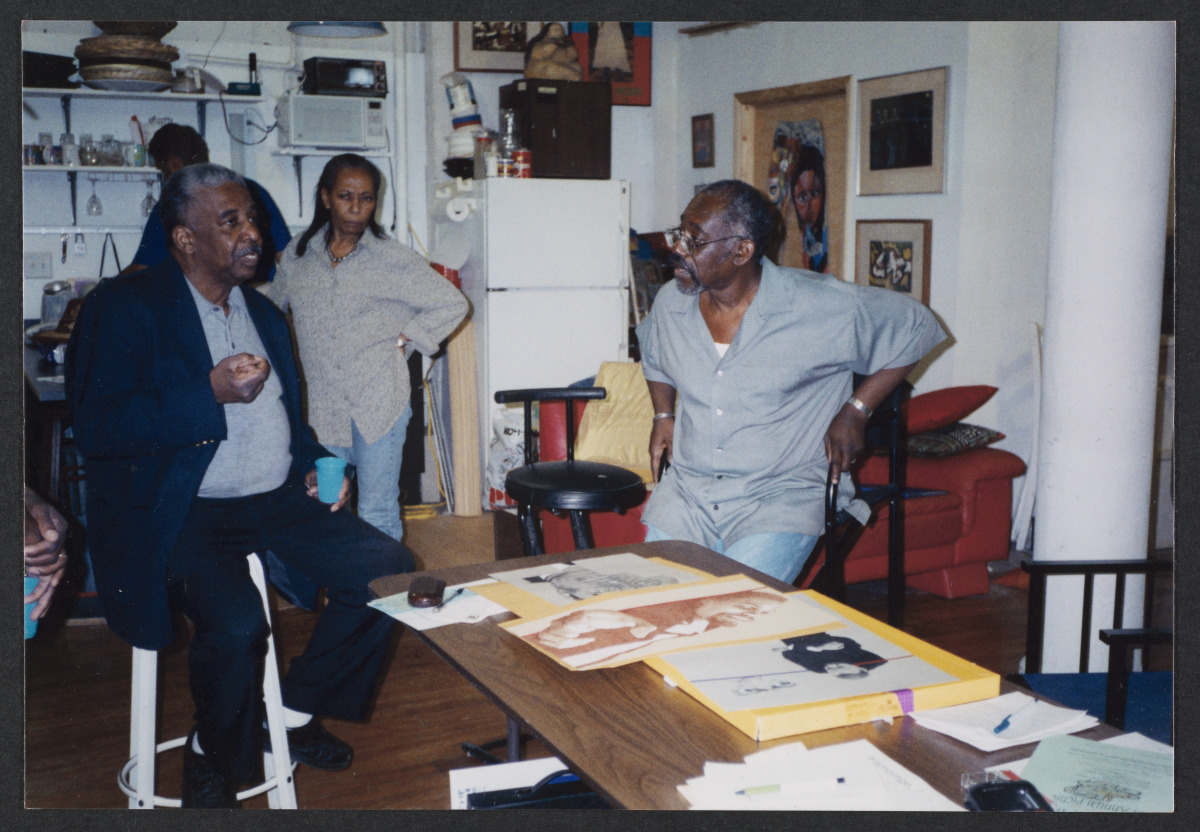

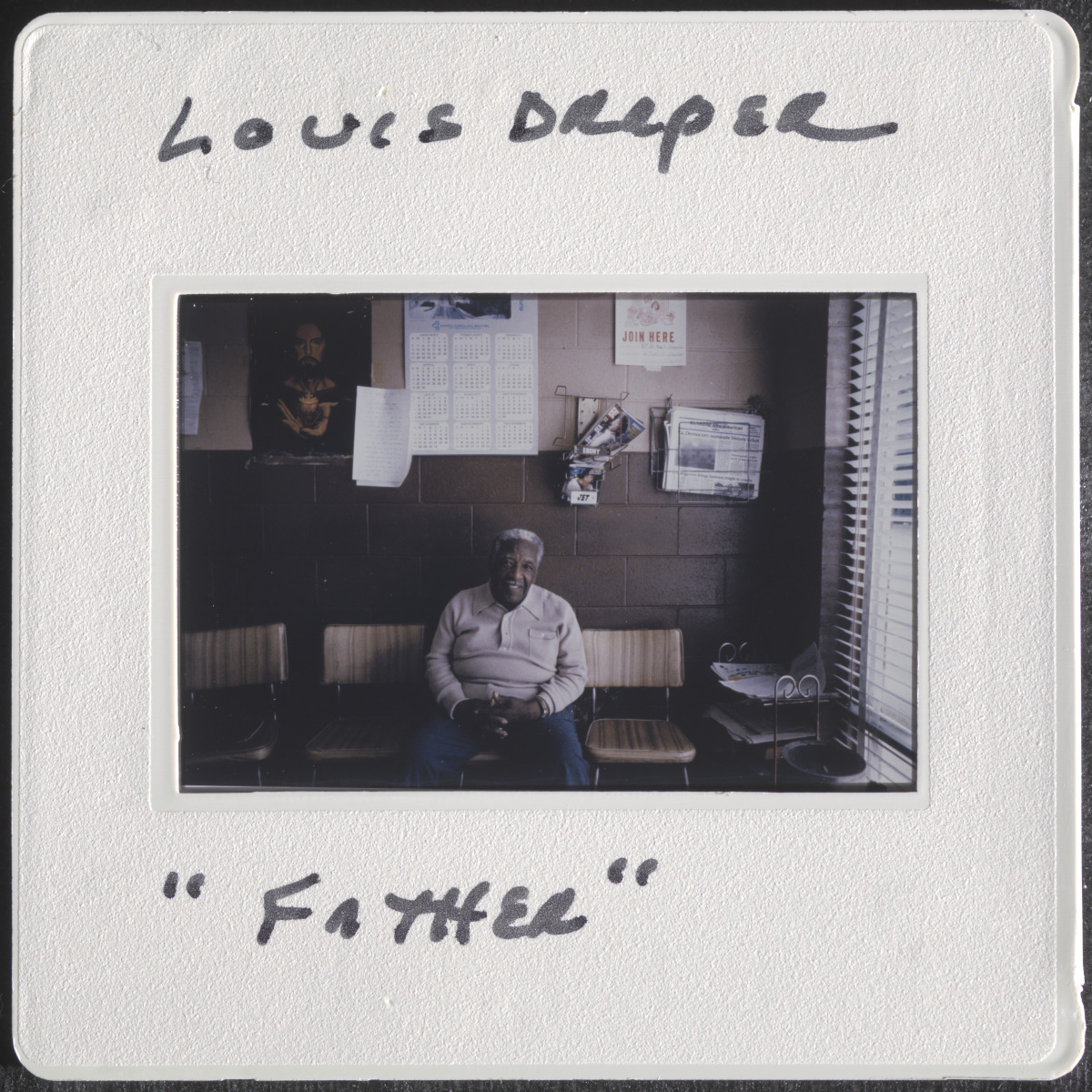

“Louis Draper: The Character of Everyday People, A Conversation with Nell Draper Winston.”

Blackbird, Virginia Commonwealth University,

blackbird.vcu.edu/v14n1/gallery/draper_l/interview_page.shtml. Accessed 12 Dec. 2019

“Malcolm X.” Biography.

www.malcolmx.com/biography/

“Medgar Evers.” FBI.

www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/medgar-evers.

Mendell, David, and Wallenfeldt, Jeff. “Barack Obama.” Encyclopædia Britannica.

Last modified November 27, 2019. www.britannica.com/biography/Barack-Obama. Accessed 5 Dec. 2019.

Parrott-Sheffer, Chelsey. “16th Street Baptist Church Bombing.” Britannica.

www.britannica.com/event/16th-Street-Baptist-Church-bombing.

“School Busing.” Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

www.virginiahistory.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/civil-rights-movement-virginia/school-busing\. Accessed 12 Dec. 2019.

Smith, Sharron, “Private Schools for Blacks in Early Twentieth Century Richmond, Virginia”

(2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1477068460.

http://doi.org/10.21220/S2D30T

“The Birmingham Campaign.” PBS.

http://bcc2.lunchbox.pbs.org/black-culture/explore/civil-rights-movement-birmingham-campaign/.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Jesse Jackson.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Last

modified October 4, 2019. www.britannica.com/biography/Jesse-Jackson. Accessed 5

Dec. 2019.

“The Family of Man.” The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2429.

Accessed 20 Dec. 2019.

“Virginia E. Randolph, a Teaching Pioneer.” African American Registry,

www.aaregistry.org/story/virginia-e-randolph-a-teaching-pioneer/.

Wadland, Mary. “Brown V. Board Of Education – 65 Years and Counting.” Zebra Press, 22 Feb.

- thezebra.org/2019/02/22/brown-v-board-of-education-65-years-and-counting-2/.

Wallenfeldt, Jeff. “Los Angeles Riots of 1992.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Last modified April 22,

- www.britannica.com/event/Los-Angeles-Riots-of-1992. Accessed 5

Dec. 2019.