Many people consider Paris the “cradle of street photography,” a reference to an approach that, loosely defined, focuses on spontaneous images of daily life in urban areas. This exhibition looks at the work of three photographers—each roughly a generation younger than the next—who worked within this tradition while developing their own distinct visions: Robert Doisneau (French, 1912–1994), Édouard Boubat (French, 1923–1999), and Joel Meyerowitz (American, b. 1938). Although these photographers traveled throughout the world, this exhibition features their images of France —primarily those of Paris—as an homage to street photography.

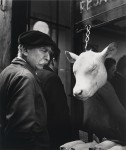

Born in a working-class neighborhood in Paris, Robert Doisneau photographed aspects of the city he knew best and captured what he considered a vanishing way of life. After a few international assignments early in his career, he declined an invitation to join the prestigious international photography cooperative Magnum, explaining that when he worked in other countries, his subjects inevitably looked too exotic. Instead, he chose to emphasize his own local knowledge. “I am part of the environment of Paris. I can be seen with my old cap pressed down around my ears when it’s cold. I am part of the setting. I know it.” Out of this rootedness in one community, he shaped an artistic philosophy that treated the city as a series of cinematic sets:

Often, you find a scene, a scene that is already evoking something—either stupidity, or pretentiousness, or, perhaps, charm. So you have a little theatre. Well, all you have to do is wait there in front of this little theatre for the actors to present themselves. I can stay half a day in the same place. And it’s very rare that I come home with a completely empty bag. (Dialogue with Photography, 1992)

The humor that frequently emerges from Doisneau’s images attests to his familiarity with his environment as well as to his ability to communicate a compelling narrative in a single frame.

Less well known than Doisneau, Édouard Boubat also spent the majority of his life in Paris and was part of the same milieu. Boubat subscribed to a more romanticized notion of chance, describing his approach as reliant on his awareness that a singular photographic moment awaited him. In 1988 he discussed his most famous photograph, The Little Girl with Dead Leaves, which is featured in this exhibition:

One fall morning after the war, I am walking through the Luxembourg Gardens, I meet “The Little Girl with Dead Leaves”; she is there for herself and for me: my first picture awaits me. If I were to go through those gardens year after year I would never meet her again. (Édouard Boubat: Pauses, 1988)

Boubat prided himself on his ability to capture his final image after taking very few pictures (and often just one).

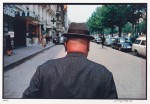

Joel Meyerowitz began photographing American cities in the 1960s alongside Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and Diane Arbus. Openly indebted to Robert Frank’s influential The Americans—a gritty portrayal of 1950s America—Meyerowitz also aimed for a certain “toughness” in his images. “Something that came from your gut, out of instinct, raw, of the moment, something that couldn’t be described in any other way.” (Bystander: A History of Street Photography, 1994).

When he turned his camera on the streets of Paris in 1983, Meyerowitz signaled his awareness of the legacy of Doisneau and Boubat, as well the work of two other French photographers who influenced them—Eugène Atget (1857–1927) and Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004). His use of color adds another layer to this photographic tradition, while it also marks a transition to a younger generation.

Event Has Concluded

Photography Collection Fact Sheet

Posted on October 3, 2013

VMFA has built a collection of some 1,200 photographs during the past 75 years. Read more