The research on the African Collection being carried out as part of the recently awarded Andrew W. Mellon grant is continuing to produce new insights into the objects in our collection. For example, as part of a comprehensive study of the Ethiopian crosses in our collection, 19th to 20th century hand cross (#2015.319) has undergone a battery of scientific testing to determine its construction and composition.

One of the first discoveries during this testing was that the cross is made of an alloy of silver, copper, and zinc– not iron, as was listed in the museum records.

Depending on how they were formed, objects made of metal can have very different microstructures- or grain patterns. Examination of our silver cross under the microscope revealed a clear microstructure at its surface, which manifests as a silver background with small black branched shapes known as dendrites, a term that comes from the branching structure of trees, dendrons in Greek. The presence of these dendrite crystals tells us that the cross was made by casting- accomplished by pouring the molten metal into a mold.

Ethiopian crosses like this one would have likely been made using the lost-wax technique, whereby a model is created in wax and then a modified clay investment material would have been applied over the model, creating the mold. When the mold and wax were heated, the wax could be poured out, leaving a hollow for the molten metal to be poured into.

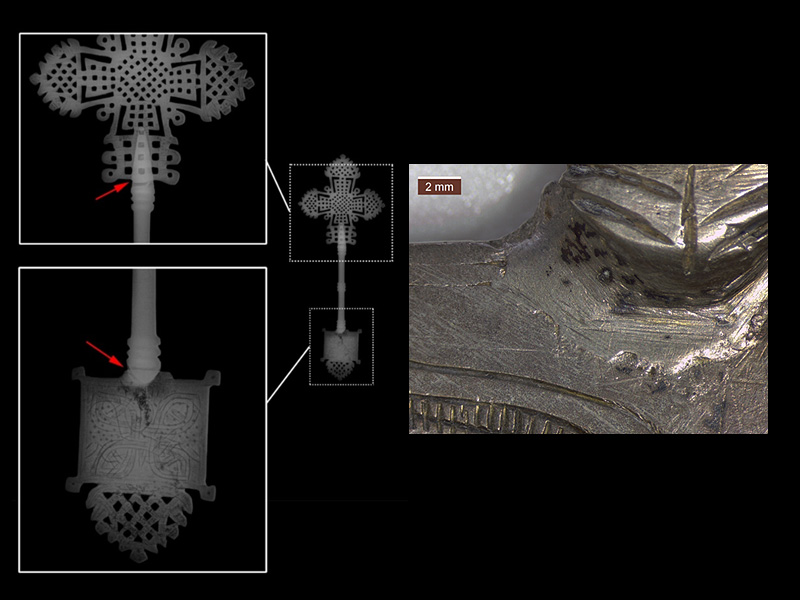

X-radiography and microscopic examination of our silver cross reveals that it was actually cast in three separate pieces: an openwork Greek cross at top, a solid rectangular handle, and a flat tabular section at the bottom that terminates in a triangular section of openwork design. The x-radiograph of the cross shows the distinct edges where the cross and tabular sections end. The handle is notched at either end so that the two pieces fit in the openings.

The top and bottom of the handle were then joined to the cross and tabular end by soldering, a method of using molten metal (solder) to secure the two pieces together. Upon cooling/hardening, the solder creates a permanent join. The solder join is clearly visible under the microscope where the bottom of the handle meets the tabot (see image).

While the openwork design on the top and bottom sections of the cross were executed in the casting, the additional surface decoration on the three components was carried out primarily by engraving. The marks from the graver/chisel are clearly discernible under high magnification (see photomicrograph). The short overlapping strokes at the curves indicate that a graver tool was likely used in a chisel handle with a chasing hammer as each blow with the hammer is visible as a separate, overlapping mark.

While the study of these crosses is ongoing, we’ve already begun to add a great deal of information to our museum records for the individual objects. Once we’ve studied the whole collection, it’s hoped that we’ll be able to distinguish patterns in composition and fabrication technique that will add to our understanding about these crosses and the contexts in which they were made.