In today’s digital age, every owner of a social media account serves as their own minister of propaganda. With each shared photo, observation, and announcement, we control our image and shape the way others perceive us. But even back in Napoleon’s day, paintings, clothing, decorative arts, and political cartoons served as propaganda tools. Napoleon: Power and Splendor explores the ways the Emperor used these arts to legitimize his reign after the French revolution.

On Friday, August 3, from 6 to 9 pm at VMFA, Secretly Ya’ll, a local storytelling organization, invites Richmonders to share their own stories of self-propelled propaganda in “Audacity—Stories of Pomp & Propaganda.” “We are looking for stories of times when the face that you presented to the world was, perhaps, a wee bit, uh, contoured from reality,” the group states. “Times when it seemed more useful to fabricate or hyperbolize certain attributes, facts, facets, and not others . . . moments when it was fun to boast, brag, or gloat, but perhaps afterwards realized that all that hot air [and or “duck face”] didn’t really reflect the ‘real you.’”

We asked Dr. Colleen Yarger, VMFA’s curatorial assistant for European art and the Mellon collections, to share some of the best examples of propaganda from Napoleon: Power and Splendor.

Portrait of Napoleon, Emperor of the French, in Ceremonial Robes, 1805, François‐Pascal‐Simon Gérard (1770– 1837), oil on canvas. Château de Fontainebleau‐Musée Napoléon I. Photo © RMN‐ Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY / Gérard Blot

By depicting Napoleon in the same way past monarchs had traditionally been depicted—complete with ermine robe, crown, throne and scepter—this iconic portrait appropriates the visual language of the past to legitimize Napoleon’s reign as Emperor. “He is trying to convince the viewer that he is an Emperor, equal to or above those across Europe,” Yarger says. “It is quite a transformation.”

Table Called “of the Imperial Palaces,” Later “of the Royal Palaces,” 1811–14, altered between 1814 and 1817, Sèvres Imperial Manufactory, tabletop decoration painted by Jean‐François Robert, hard porcelain, gilt bronze. Private collection. Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s

This spectacular table is symbolic of France’s artistic superiority. Previous to its creation, porcelain was used to make functional tableware and small decorative objects, many of which can be seen in the exhibition. To create a table from porcelain was, at the time, “pushing the limits of the medium with the technology that was available at the time,” Yarger says. “It is a miracle that it exists. The people who would have seen it would have recognized the technological achievement that it was. It showed that now, Napoleon has the superior army of artisans that are taking over and dominating the field of cultural arts.”

Jacket from the costume of a Grand Master of the Hunt, worn by marshal Berthier, Prince of Neufchatel, 1804, attributed to the workshop of Auguste-Francoise-André Picot, Paris, Musée de l’Armée. Photo by David Stover, ©Virginia Museum of FIne Arts

Napoleon instituted a blockade of English fabrics and reestablished France’s luxury trades, which had gone dormant after the French revolution. It was strongly recommended that all of the clothing worn at his court had to be made from fabric produced by the silk manufacturers in Lyon. “This jacket embodies the reinvigoration of that particular trade,” Yarger says. “The garments were meant to be spectacular to behold. Today, you might liken it to watching the Academy Awards. Napoleon was looking for a visual vocabulary that was the very best and the most sumptuous as well as a stimulus for the French economy.”

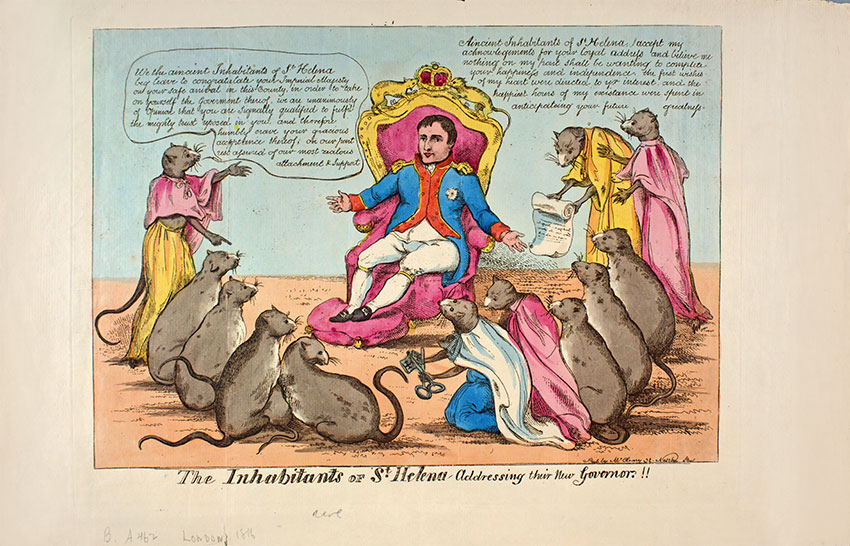

The Inhabitants of Saint Helena Addressing Their New Governor!!, ca. 1815, William McCleary (active Dublin 1799– 1820), coloured etching. McGill University Library and Archives, Rare Books and Special Collections, Montreal

Napoleon: Power and Splendor includes numerous satirical political cartoons, a classic tool of propaganda. This British cartoon ridicules Napoleon “in his demotion from Emperor to someone who is roughing it in one of the most inhospitable places on the face of the planet,” Yarger explains.“ In England, they were laughing at Napoleon’s downfall from grace. It’s propaganda from the other side.”