Jacob van Ruisdael (Dutch, 1628/1629-1682), The Great Beech, with Two Men and a Dog, ca. 1651-55, Etching, Promised Gift of Frank Raysor, L.139.2010.12

This is the fourth in a series of blog posts discussing highlights of the exhibition A Celebration of Print: 500 Years of Graphic Art from the Frank Raysor Collection currently on display in VMFA’s Mellon Focus Galleries. Admission to this exhibition is free. In this post collector and donor Frank Raysor contributes to our knowledge of the various techniques in the exhibition

My collection has many examples of the various printmaking methods that have been used by artists over the centuries. But it also contains within those defined techniques, different approaches that produce dramatically different visual results. These distinctions can be found among both etchings and drypoints.

Stopping-out involves covering over with protection, lines that are intended to be lighter, like the background of a landscape, and then subjecting the plate to further acid baths to strengthen the lines that the artist wants to be darker.

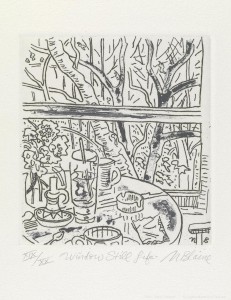

A perfect example of this is the Ruisdael, which was probably treated with only two acid applications – one for the background, which was then “stopped out,” and a further one for the foreground, which has the visibly stronger lines. Such a simple approach could be almost child-like in other compositions, but here is works well, because the emphasis in on the tree. By contrast, Hollar’s “Prague” must have had numerous stoppings-out, because the gradations among lines in the fore-, middle- and backgrounds are very nuanced, and it’s impossible to tell how many acid treatments were applied. For other examples of skillful stopping-out, consider the Claude, the Kolbe, any of the Bracquemonds or Meryons, and the Corot (where we know that Bracquemond assisted his friend Corot with the biting). Finally, for a example of an effective etching that did not involved stopping-out at all, examine the Blaine, where all the lines are of equal weight.

Nell Blaine (American, born Richmond, Virginia, 1922-1996), Window Still Life, 1986, Etching, Promised Gift of Frank Raysor, L.139.2010.78

In drypoint, where acid is not employed, similar effects can be achieved by the artist’s use of different pressures of the tool upon the metal, to create deeper or shallower lines. Good examples of superb drypoint skills are found in Haden’s “By-Road,” Bone’s “Building,” and especially in the Cameron. By contrast, the Avery displays equally strong drypoint lines, because the artist wanted a flat aspect to this modernist composition.

–Frank Raysor, guest blogger